Malaysia Population Research Hub

National Family Planning Programme

The evolution of population policy in Malaysia began from the period of the First Malaysia Plan (1966-1970) when high fertility during the post war period prompted a new policy. This led to the passage of the National Family Planning Act No. 42, 1966 and the establishment of the National Family Planning Board which was made responsible for the implementation of the national programme for family planning. The National Family Planning Programme was thus launched with the objective, among others, to lower the population growth rate from 3.1% in 1966 to 2.8% by 1985. The main consideration point behind the establishment of the act was that in situations where population growth is very high, this may slow down the economic growth of the country. Apart from Malaysia, other Asian countries also introduced a family planning programme to its population in the 1960s where the earliest country to introduce the programme was India around the 1950s. As a result of the introduction of the family planning programme in the 1960s, the country gross birth rate has decreased from 36.7 babies in 1966 to 31.5 babies per 1,000 population in 1985.

This directly makes the average annual population growth rate of the country declined from 3.0% per annum in 1966 to 2.8% per annum in 1980.

70 Million Population Policy

The mid-term review of the Fourth Malaysia Plan (1981-1985) represented a major milestone in the country population policy. In this review the government recognised the inter-linkages between population and development processes. It also recognised that continued population growth does not necessarily have a negative effect on development. A larger population and the increased domestic market can be beneficial in achieving national development goals, provided that the quality and productivity of the population are being constantly raised.

According to Honorable Prime Minister, the target of 70 million people is a long- term projection that is considered ideal and achievable by the country within 115 years, in 2100.

Thus, although set in the context of a very long time horizon, a specific population size of 70 million was identified as an ideal target towards which Malaysia might aim for. (The shift in emphasis can also be seen in the change of name of the National Family Planning Board to the National Population and Family Development Board.) The findings formed the population policy of 1984.

The interest in a population size of 70 million was relevant at the time. In 1984, Malaysia population was just about 15 million, whereas compared to its neighbours: Thailand 51 million, Philippine 53 million, Indonesia 159 million, Singapore 2.7 million, Vietnam 58 million; in terms of absolute GDP, Malaysia was also behind many of its SEA peers.

Table 1: Population size (million) and GDP size (USD million) of ASEAN-6 countries, 1984, ordered by increasing population size

| YEAR 1984 | YEAR 1984 | GDP (USD MILLION) |

| Singapore | 2.7 | 20 |

| Malaysia | 15 | 35 |

| Thailand | 51 | 42 |

| Philippines | 53 | 53 |

| Vietnam | 58 | 23 |

| Indonesia | 159 | 88 |

Source: World Bank

All five objectives above were recommended by the population policy of 1984. In addition, a sixth was recommended: to review present policies such as income tax and maternity benefits that tend to encourage small family sizes. In the recommendations, the population policy of 1984 has also alluded to matters of sustainable development; in particular, achieving a more equitable distribution of income and a balanced distribution of population.

It is important to note that, based on the wordings of the strategies, a distinction was made between the population policy, i.e. the policy of 1984, and a population development policy which at the time was not and had not been developed. This implied that while the size of the population was believed to be important, the population policy of 1984 recognized the equal importance and need for a population development policy. Subsequently, during the First Population Strategic Plan Study in 1992, the population policy of 1984 was reassessed.

The findings of the study revealed that, despite efforts, the TFR was dropping faster than expected.

The TFR had reached replacement level 56 years earlier than it was intended: in 2014, the TFR reached 2.1, and in 2015, had dropped below the replacement level at 2.0. In addition, history had proven that the difficulty in bringing up the TFR once it had fallen was extremely challenging. Hence, the quantitative target of 70 million to be achieved by the year 2100 was concluded to be not feasible.

The 70 million population was deemed feasible as long as a couple of assumptions continue to hold: firstly, that the target is attained within a long period of 100 to 120 years; and secondly, that the TFR declines at a clip of 0.1 point every 5 years until it reaches replacement level around 2070. The population will then reach 70 million by 2100 and stabilise at around 73 million by 2150. It is important to consider that at the time of the policy, the total fertility rate of Malaysia population was already declining. Although the TFR was at 3.9 in 1984, it was declining at such a rate that it was projected to reach only 39 million by 2150. The objective was then to delay the decline of the TFR to replacement level by 40 or more years.

In order to achieve the 70 million vision, 26 strategies were suggested. The 26 strategies ensured broad coverage across the social economic landscape. In addition, it was also explicitly stated that immigration was not recommended as a viable strategy.

| Objective | Strategy |

| To take into consideration and coordinate the differential growth of population and development of the country income and productivity | 1. Integrate economic development policies with population development policy. 2. Integrate economic development policies with manpower policy. 3. Integrate economic development policies with social policy. 4. Integrate economic development policies with food, water and agriculture policy. 5. Integrate energy policies with population development policy. 6. Integrate environment policies with population development policy. 7. Develop comprehensive and well-coordinated programmes for family development in order to promote women to continue to participate economically and provide assistance to fulfil their family responsibilities. 8. Provide integrated services to improve family welfare, child care, and improve family income; incorporate into these schemes family life education stressing on values of the traditional family, marriage, and childbearing/childrearing; and integrate these value systems into the school curriculum. 9. Develop childcare facilities and facilities for marriage counselling. 10. Consider the effects and impacts of any new programmes and legislations on the family. |

| To strengthen overall health and other social services for poor areas, bringing about a decline in mortality and morbidity | 11. Strengthen health services to improve both preventive and curative activities, emphasising maternal and child health in particular perinatal care. 12. Expand and strengthen school health services to cover all children from childcare centres and kindergartens to primary schools. 13. Review school supplementary feeding programmes in order to improve coverage and nutritional quality. 14. Strengthen health education programme generally and nutrition education programme in particular. 15. Provide adequate and appropriate housing, safe water supply, improve sanitation and general environmental conditions to all poor areas. 16. Continue family planning programme but with greater emphasis on spacing of births and expand services offered to include infertility management, genetic and marriage counselling and family life education. |

| To closely monitor population dynamics and rate of fertility decline | 17. Enhance vital registration system in data collection, in particular Sabah and Sarawak, and the collation, analysis, publication, dissemination, and utilisation of the data. 18. Improve methodology in collating and analysis of census data so that they are immediately available for use. 19. Maintain population data at the lowest administrative levels, such as at the village and town levels. 20. Develop a comprehensive economic-demographic model to evaluate economic implication of alternative population growth. 21. Promotion of population and development research in general. 22. Set up a permanent committee to study the current demographic situation of the country, which include monitoring current trends and patterns of population growth and distribution, population characteristics, and magnitude of population movement. 23. Set up a permanent committee to recommend to the government the population development programme and policy thrusts for the next five years beginning in 1985 within a context of short, medium and long term perspectives. 24. Set up a permanent committee to identify and evaluate research areas and research gaps in population and development related research activities. |

Source: Malaysia Population Policy 1984

Strategic Plan Study for Implementation of National Population Policy

NPFDB has evaluated the achievement of the 70 Million Population Policy through the implementation of the Strategic Plan Study for the Implementation of the National Population Policy in 1992. The findings suggested that the quantitative objective of this policy (70 million population) may not be achieved due to the decline in population fertility faster than what to expect. The total fertility rate (TFR) had reached replacement level 56 years earlier than it was intended: in 2014, the TFR reached 2.1, and in 2015, had dropped below the replacement level at 2.0.

Through this study, the population of the country is expected to reach only about 45 million people in 2100 (medium-variant projection).

Therefore, this study recommended that the planning of population and family development programmes towards producing quality population and strong family institutions is more important than achieving a mere quantitative target. In September 1994, the United Nations has advocated the International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD) in Cairo, Egypt. As a result of the conference, a population action plan for 20 years has been developed and adopted by 179 member states including Malaysia. Beginning of the year, all population-related activities in the country have been guided by the document.

Second Population Strategic Plan Study

In assessing the effectiveness of the strategy as well as the performance of the existing national population and development programmes as well as activities, in 2009, NPFDB has conducted the Second Population Strategic Plan Study.

The main findings of this study were the fertility rate of population has declined faster and was expected that the replacement level of population will be achieved by 2015.

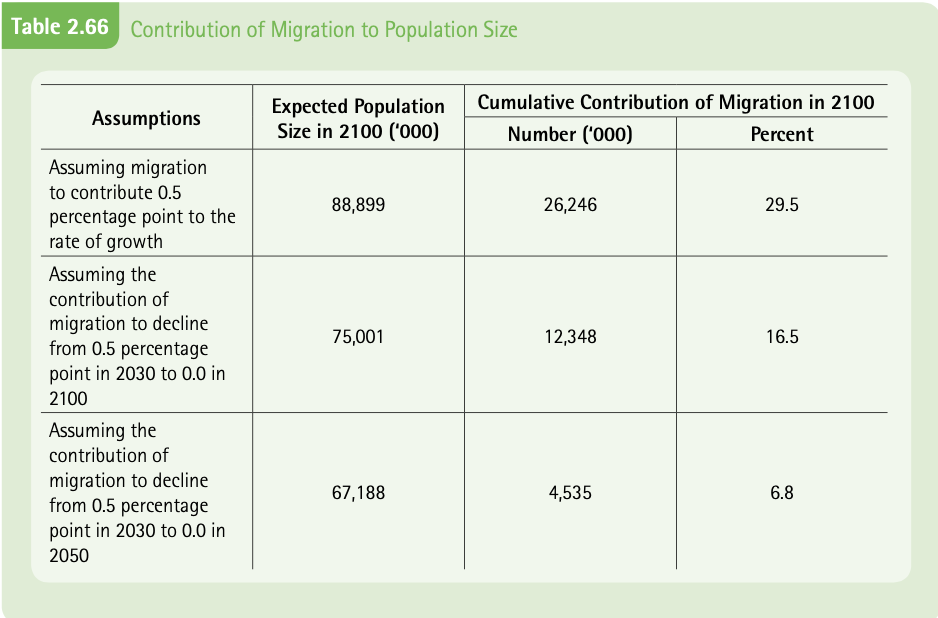

Although this study found that population fertility rates have declined, the country at that time was still experiencing high population growth at the level 2.6% per annum for the period 1991 till 2000. And this study projected that the population was able to reach nearly 75 million people in 2100 (assuming that the contribution of international migration declines from 0.5% in 2030 to 0.0% in 2100).

With the 1992 study concluded, the Malaysia population policy began to shift from one principally based on a quantitative target to one that emphasised the qualitative. In light of the number of major policy changes that have taken place in the country, namely the National Development Policy and Vision 2020, the main thrust of Malaysia future population would shift towards sustaining population growth in balance with resources and development. (The shift was not opposed to the population policy of 1984 as it also stressed the primacy of human resource development, as shown earlier.) In other words, there was a realisation that it was quality, rather than quantity, that mattered.

The point to be made was that it was not necessary to intervene to prop up fertility. Interventions to influence fertility do not appear to be needed. It is more important to enable couples to plan their families according to their resources. Family planning services in Malaysia are thus provided based on the policy of non-coercion for the promotion of maternal and child health.

In 2009, the Second Population Strategic Plan Study was carried out with this in mind. While the study showed that Malaysian families were getting smaller and the TFR was continuing to drop at a rapid pace, the study with equal (if not more) importance emphasised the various qualitative aspects of population development that needed to be addressed. In particular, some of the recommendations included paid paternity leaves, paid compassionate leaves in case of children sickness, more flexible working hours, childcare facilities at the workplace, subsidies for childcare costs incurred by working mothers, increased tax concessions for dependent children, programmes to encourage husbands to be more fully involved in childrearing and household chores, and address the unmet needs for contraception, among others.

A Review of The National Population Policy: Strategic Action Plan for Sustainable Development Towards 2030

In 2017, NPFDB conducted A Review of the National Population Policy: Strategic Action Plan for Sustainable Development Towards 2030 to identify current issues relating to population and thus provide a strategic action plan in the pursuit of achieving sustainable development goals by 2030 in line with the Post 2015 United Nations Development Agenda theme titled Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. All issues or challenges as well as the policy recommendations reported in this book are based on the findings of A Review of the National Population Policy: Strategic Action Plan for Sustainable Development Towards 2030.