Malaysia Population Research Hub

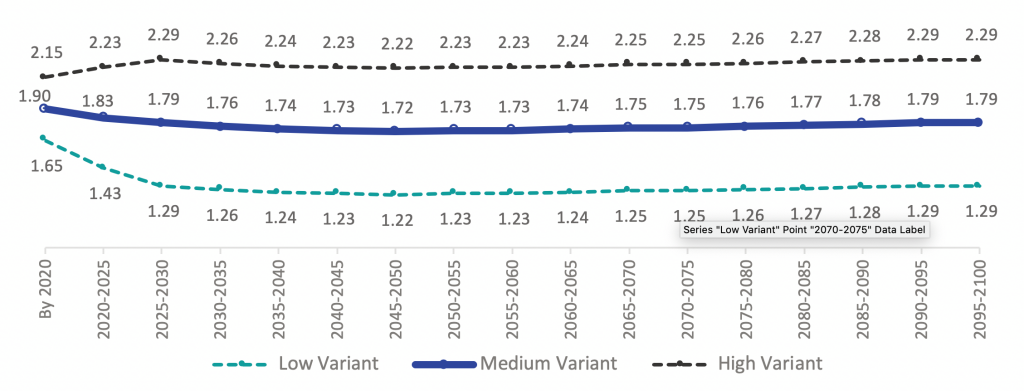

The rapid decline of the TFR in the past decade and a half has accelerated the nation’s ageing process. The TFR will likely stay between 1.9 and 2.0 by 2020 (and fall below 1.9in the coming decade), based on the going trend.

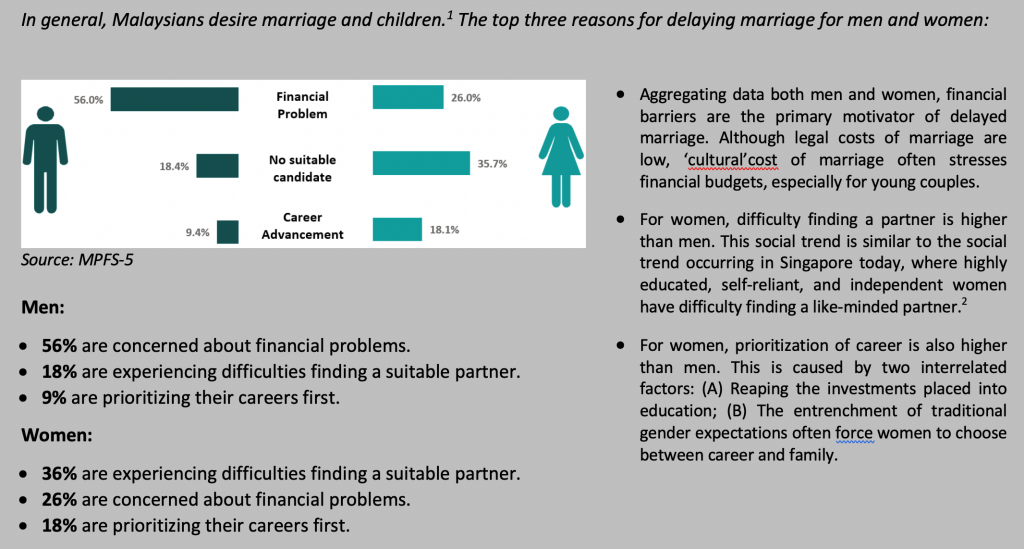

Malaysia’s TFR has continued to decline over the past decades, primarily due to delayed marriages (and subsequently delayed childbirth), as well as families trending towards small-sized norms.

Within ASEAN, Malaysia ranks among the bottom-4 countries with lowest TFR.

Malaysia’s TFR in 2016 was 2.0—already below the ratio needed to replace its population (i.e. TFR of 2.1). From 1960 to 2000, the TFR declined at a rate of 1.8% per year; however, from 2000 to 2015, Malaysia experienced its fastest TFR decline since then, the TFR declined at a rate of 3.1% per year from 2000 to 2010, and at a rate of 2.5% per year from 2000 to 2015.

The rapid increase in the TFR decline over the past decade and a half has played a large part in accelerating ageing process of the nation.

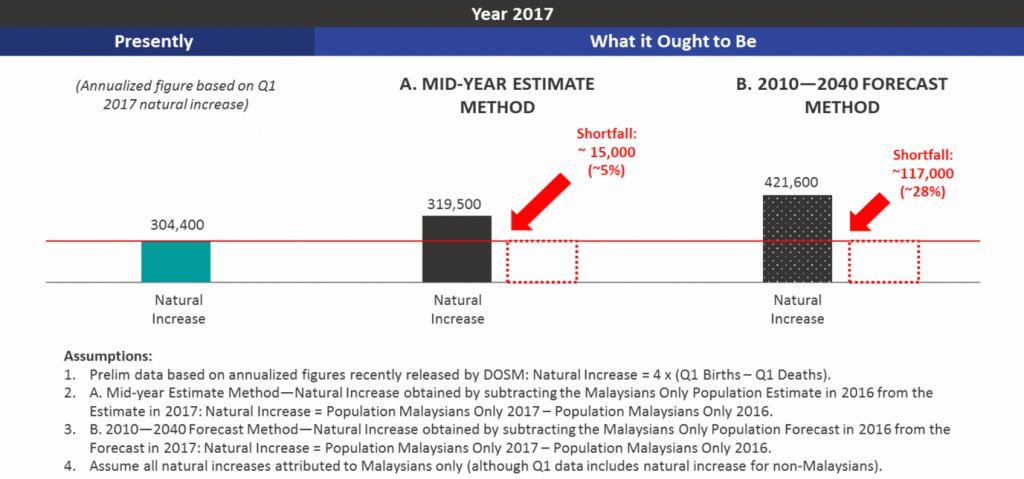

Preliminary comparison of 2017 Q1 natural increase with previously forecasted numbers.

Source:Ipsos Analysis based on DOSM Population Estimates 2016 & 2017 and Forecast 2010—2040

Given the current scenario, the TFR will likely stay between 1.9 and 2.0 by 2020, falling further away from the replacement ratio. The present projection by DOSM anticipates the TFR to fall to 1.78 by 2040; based on UN’s medium variant projection, Malaysia’s TFR may fall below 1.8 as early as 2030, and will fall closer to the lower range of 1.7 by 2040 and 2050. Based on one estimation model, it appears that the TFR situation may fall short of present projections, although this is still too early to tell. There is a risk of TFR falling below 1.7 between now and 2050. Although it is unlikely that Malaysia’s TFR will fall into very low TFR levels, i.e. 1.5 and below, the following observation remains true: that it is increasingly challenging to raise TFR levels the further it falls. Even at present TFR projections of stabilizing around 1.7 to 1.8, Malaysia will likely experience demographic challenges. The goal, thus, is to ensure that TFR levels remain at or near the replacement ratio, i.e. 1.9 to 2.1, which is easier to achieve now than later.

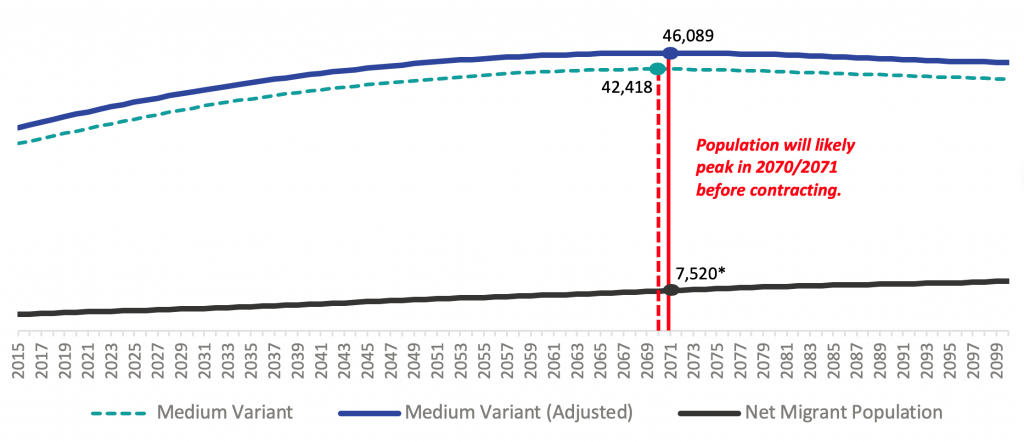

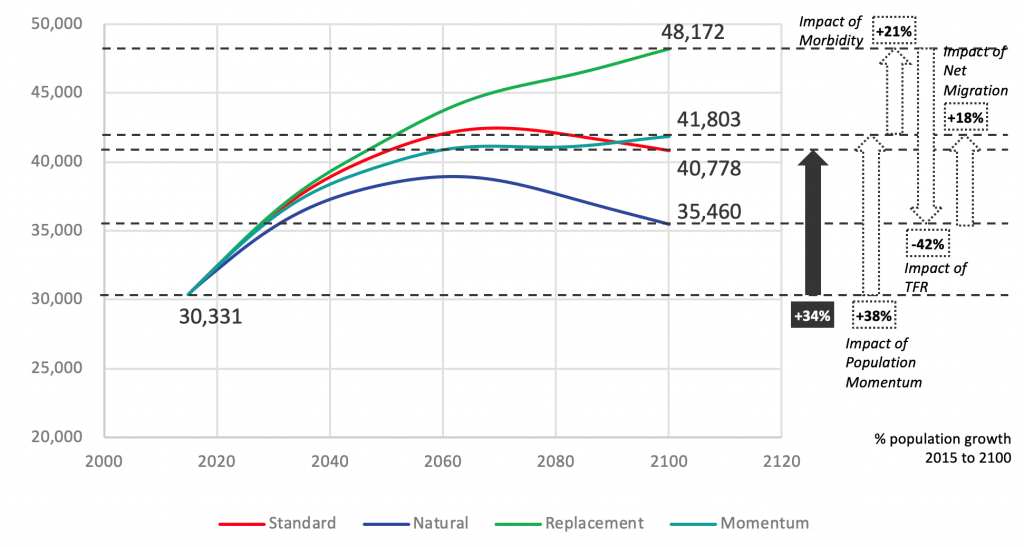

(2) Going at the current rate and without any intervention in addressing the declining TFR, Malaysia could potentially experience its first population shrinkage by 2071—2072.

Projected population peak and contraction, Malaysia (UN Projection)

Source: Ipsos Analysis, based on World Population Prospects Data:2015 Revision, United Nations, normalized with DOSM data

Note: *Figure for net migrant population derived from difference between medium variant (adjusted) and UN population projection zero migration variant.

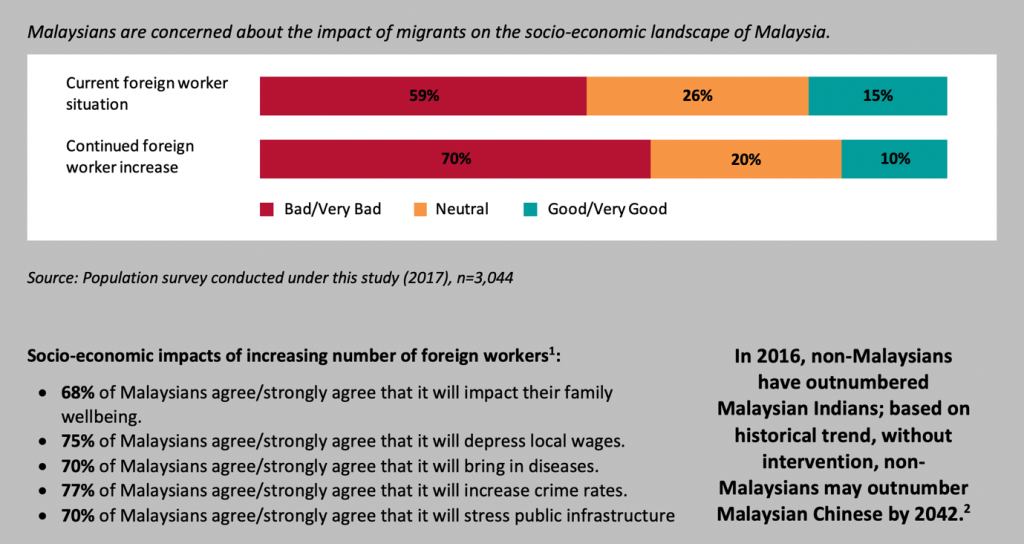

In 2016: Non-Malaysians, 3.3 million; Malaysian Indians, 2.0 million; Malaysian Chinese, 6.6 million (DOSM Population Estimate 2016). By 2042: Non-Malaysians, 7.63 million; Malaysian Indians, 2.31 million; Malaysian Chinese, 7.57 million (Ipsos Analysis, extrapolated based on linear historical best fit of DOSM Population Estimate data, 2010 to 2016).

The projection reveals two important implications for policy making: (1) Assuming that the TFR continues to dip below the replacement ratio and maintains at the 1.7—1.8 level mark, Malaysia would need to at least double the number of migrants, from an estimated 3.3 million in 2016 to more than 6 million, in order to reach the peak population of 45 million by 2070/71; (2) To prevent population shrinkage, even more migrants would be needed.

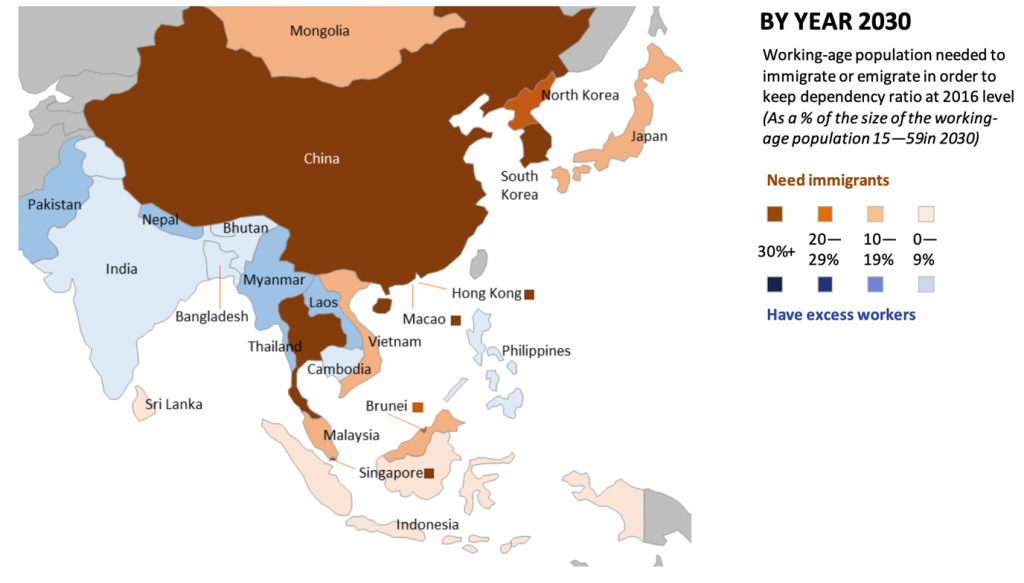

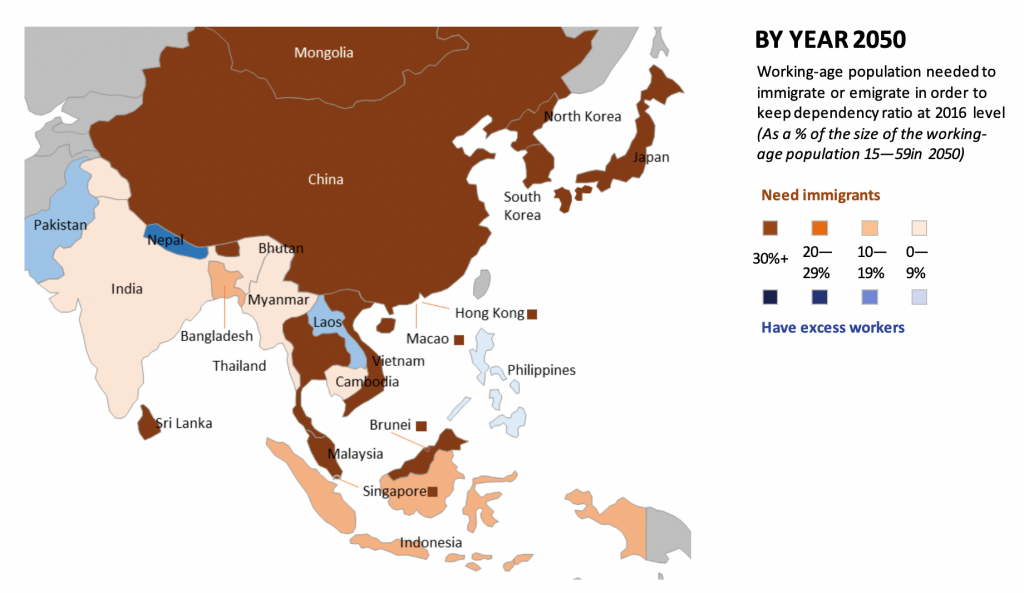

The usage of migration as a population growth level will not likely be a sustainable strategy, due to the following reasoning: (1) A migration strategy will necessitate the movement of population from countries with ‘excess workers’, i.e. countries with low dependent ratios, typically countries around the Asia and Middle East regions; (2) By 2030 and 2050, most of the countries with ‘excess workers’ will be ageing as well; (3) Thus, these countries will be competing to keep their workers within their borders and services.

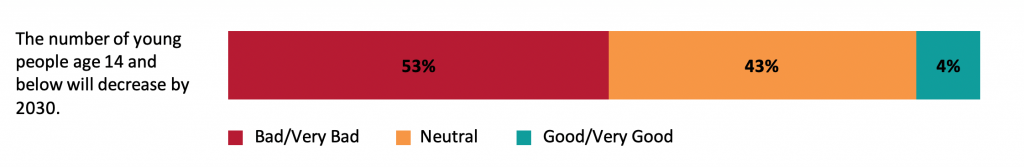

Most Malaysians believe that a declining younger population is a negative development.

Source: Population survey conducted under this study (2017), n=3,044

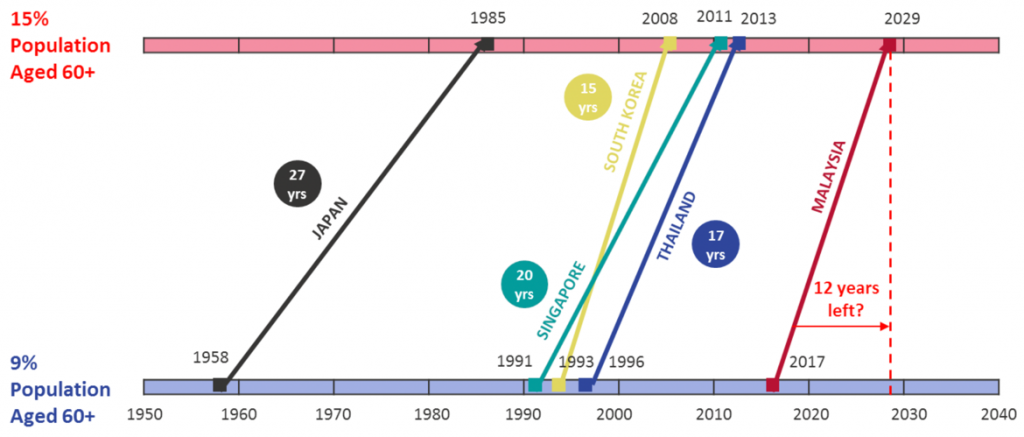

Comparing the number of years it took for the following countries to reach ageing status (defined as 15% of the population are aged 60+) since the formation of constitutional governance/independence: (A) Japan took 38 years; (B) South Korea took 60 years; (C) Singapore took 46 years; (D) Thailand took 81 years. Based on latest projections, and due to the increasing rate of TFR decline, Malaysia is set to achieve ageing status by 2029, 5 years earlier than previously projected. Taken from its independence, Malaysia would have taken 72 years to reach ageing status, much slower than Japan, South Korea, and Singapore, but faster than Thailand.

However, comparing the time frame that Malaysia is at today (where 9% of its population are aged 60+) with the similar time frame that the other 4 countries experienced to reach ageing, a different picture emerges. Malaysia has only 12 years left, whereas the other 4 countries have at least 15 years or more. The mismatch in the overall time it took to age since independence and the ‘last mile’ is due to the fact that Malaysia’s TFR has decreased much faster over the last decade, compared to the previous decades.

Areas where Malaysians feel that the nation is least prepared[1]:

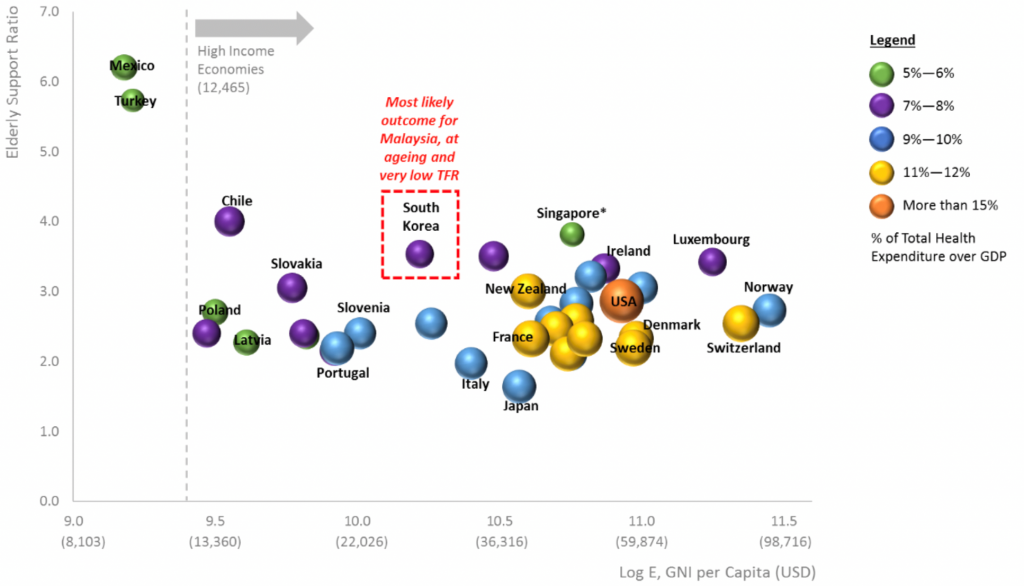

(4) The rapid ageing will be a challenge for Malaysia, if it does not achieve high-income status at a high-enough level. Comparatively, Malaysia is ageing closest to South Korea’s trajectory; Malaysia will need to achieve a GNI per capita of between USD 20,000 to USD 25,000 by 2029.

Japan, South Korea, and Singapore all achieved high-income status at a high level when they achieved ageing status (Thailand did not). From a benchmarking perspective, Malaysia would need to achieve similar levels in order to experience the same economic growth in an ageing condition.

Elderly Support Ratio (2015)—GNI per Capita (2015)—Percentage Total Spend on Healthcare (2014) of OECD countries

Source: Ipsos Analysis based on UN World Population Prospects, WHO Global Health Expenditure Database, World Bank

Note: *Singapore is not an OECD member country

Between the three countries, South Korea is the most similar to Malaysia’s present situation, in terms of: (A) The length of time South Korea took to age; (B) The GNI per capita of South Korea in 1993 (i.e. Malaysia’s present ageing condition, 9% population aged 60+); (C) The population of South Korea in 1993 (44 million) ; and (D) The relative recent year South Korea achieved ageing (in 2008). By the time South Korea achieved ageing in 2008, it had increased its GNI per capita by more than 2.5x.

Malaysia’s current GNI per capita is between USD 10,000 to USD 11,000. Going by the South Korean benchmark, Malaysia will need to achieve a GNI per capita of around USD 20,000 to USD 25,000 by 2029. This will allow Malaysia to maintain a higher total healthcare expenditure of 7—8% of GDP, with all other things considered, which is South Korea’s present healthcare expenditure spending. At a higher GNI per capita income of USD 36,000 to USD 60,000, Malaysia will be able to maintain a total healthcare expenditure of between 11—12% of GDP.

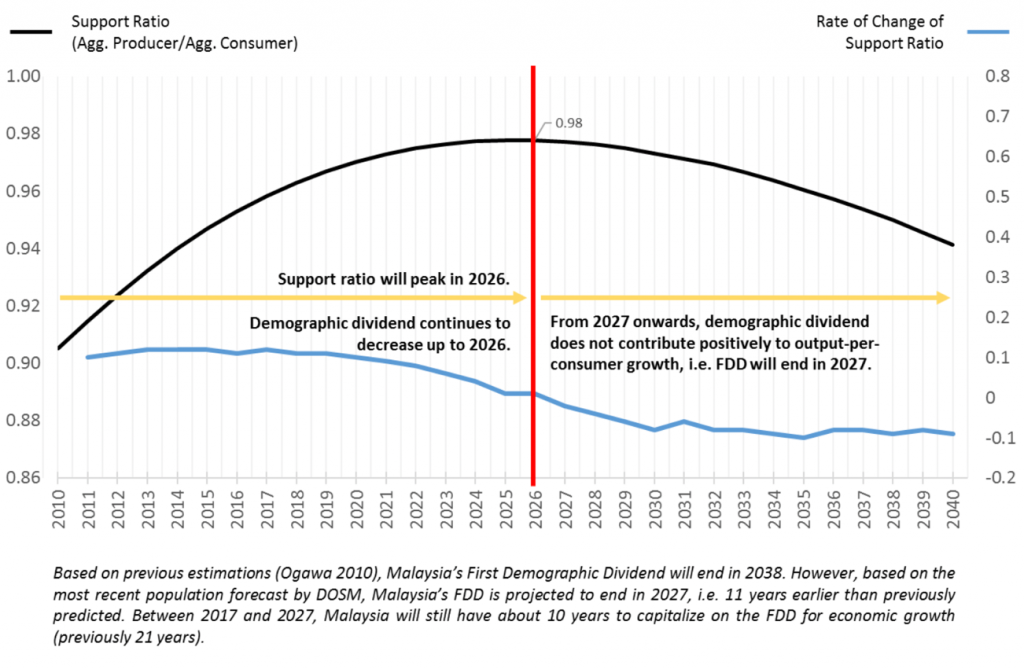

(5) To double up Malaysia’s GNI per capita, the first demographic dividend can still contribute positively to economic growth up to 2026; but beyond 2026, high productivity must become the primary driver of economic growth, and Malaysia needs to urgently invest in raising its productivity today.

Dependency ratio, Malaysia, 2010 to 2030

Source: Ipsos Analysis, based on DOSM population forecast 2010 to 2040

The dependency ratio is projected to peak between 2015 to 2020. Beyond 2020, dependency ratios will worsen, primarily due to increasing elderly dependency. The additional “free” resources generated by a large working age population over the number of dependents will gradually shrink and diminish. The contribution to economic growth due to the demographic profile of producers to dependents is the first demographic dividend (FDD).

Based on the dependency ratio, without adjusting for lifecycle consumption and production, Malaysia’s FDD will end in 2019 (elderly dependents aged 64+). However, this is rather arbitrary, as it does not account for the fact that, depending on the age group, any person may be a producer and consumer at the same time, and the relative production and consumption differs. Adjusting for lifecycle consumption and production, Malaysia’s FDD is estimated to end in 2026. The present estimation is earlier than previously predicted, which was 2038, by 12 years.

Demographic dividend (lifecycle adjusted model), Malaysia, 2010

Source: Ipsos Analysis, based on consumption and production coefficients of developing countries as calculated by Lee and Mason (2007)

Post 2026, Malaysia will need to build towards the second demographic dividend (SDD), of which its contribution to economic growth can be significantly higher than the FDD, and theoretically without limit. In order to build up a strong SDD, raising the nation’s productivity is key.

Recommendations for building up a strong second demographic dividend:

(6) Raising productivity begins with minimizing the mismatches between skills of the population and the jobs the nation is creating; perceptions about TVET needs to change, and families play an important role in changing this perception.

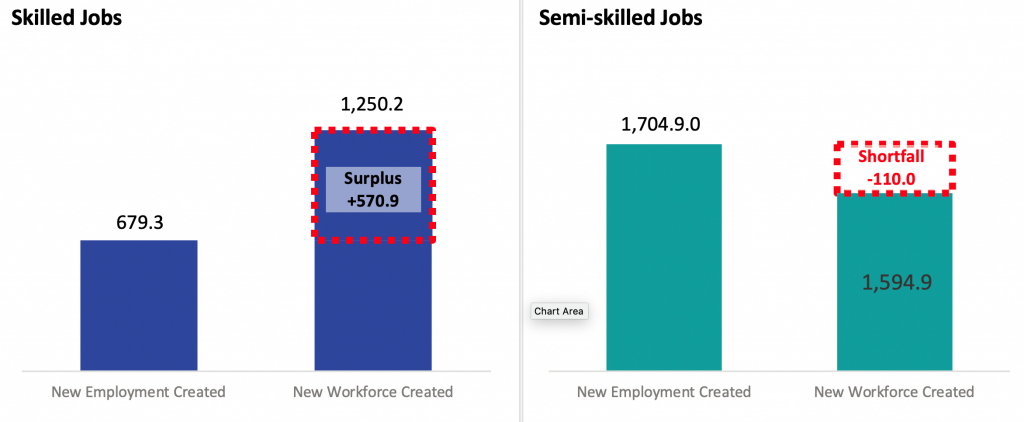

Between 2010 to 2016, there was a surplus of skilled workforce created compared to skilled jobs created, whereas there was a shortfall in semi-skilled workforce created compared to semi-skilled jobs created. The large mismatch in population skills to the jobs that have been created is not conducive to raising productivity, as large mismatches in skills to jobs imply that there is a high prevalence of underemployment or overemployment in the economy.

Total supply-demand gap for skilled and semi-skilled jobs (thousand people), Malaysia, between 2010 to 2016

Source: Labour Force Survey

Note: ‘New Employment Created’ is the difference between employment in 2016 and 2010 in the occupation skill group. ‘New Workforce Created’ is the difference between labour force + outside labour force in 2016 and 2010 in the particular skill group.

Definitions: For New Employment Created:(1) Skilled=Managers, Professionals, Technicians and Associate Professionals (MASCO Groups 1, 2, & 3); (2) Semi-skilled=Clerical & Support Workers, Service and Sales Workers, Agriculture, Forestry and Fishery Workers, Craft and Trade-related Workers, Plant and Machine Operators and Assemblers (MASCO Groups 4, 5, 6, 7 & 8); For New Workforce Created: (1) Skilled=Diploma, Degrees and equivalent; (2) Semi-skilled=SPM, STPM, Certificates and equivalent

For Malaysia, there is an overemployment of low-skilled workers in semi-skilled jobs in particular.

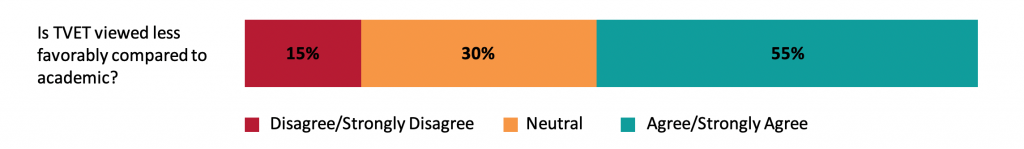

Most Malaysians agree that TVET is viewed less favourably compared to academic qualifications.

Source: Population survey conducted under this study (2017), n=3,044

In order to reduce the mismatch, perceptions about TVET needs to change. Current preference for academic—TVET qualifications is 60:40, whereas in reality, the number of academic—TVET jobs created is 30:70. Families play an important role in changing perceptions about TVET, as the biggest influencers of children’s career are their parents, often more so than educators or counsellors. Considering that about 1.3 million TVET jobs will be created under the 12 NKEA, the future economic wellbeing of families may be affected if mismatches continue to persist.

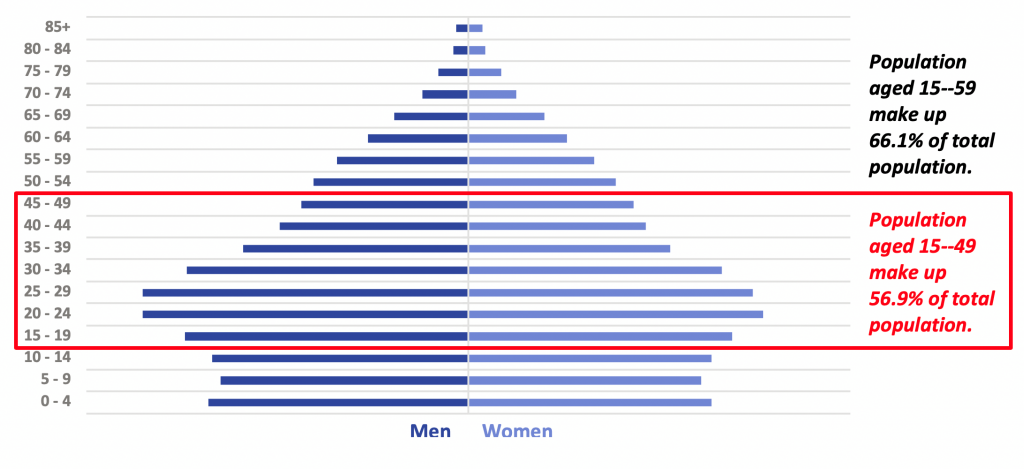

(7) TFR and Population Momentum are the two largest factors affecting population growth for Malaysia; TFR interventions should be implemented now, to take advantage of the current population pyramid.

Four factors affect population growth: (A) Total Fertility Rate; (B) Migration; (C) Mortality; (D) Population Momentum. In particular, population momentum is dependent on the structure of the population pyramid at the point of analysis. A positive population momentum implies that the population would continue growing for an extended period of time despite constant TFR, migration, and mortality.

Based on UN’s projection, the two most significant factors that determine Malaysia’s population growth are TFR and population momentum. Malaysia’s population momentum has a high impact on future population growth due to the structure of its population pyramid, which is “fat in the middle”—about 57% of the total population are aged 15—49, i.e. within the women’s fertile lifetime. TFR interventions should be implemented now, to capitalize on the population momentum for growth.

Impact assessment of population growth factors, Malaysia

Source: Ipsos Analysis, based on World Population Prospects Data: 2015 Revision, United Nations

Note: (1) Standard=Population projection, medium variant; (2) Natural=Medium variant, but zero migration; (3) Replacement=Medium variant, but TFR at 2.1, zero migration; (4) Momentum=Medium variant, but TFR at 2.1, zero migration, constant morbidity at 2010 level.

Population pyramid, Malaysia, 2016e

Source: DOSM Population Estimate

TFR interventions need to take the following into account:

(8) In addition to raising the TFR, the nation needs to urgently address the following: (A) Widening the economic base of support by raising the participation in economy building; (B) Prepare the labour force and jobs market today to support active-ageing by 2029.

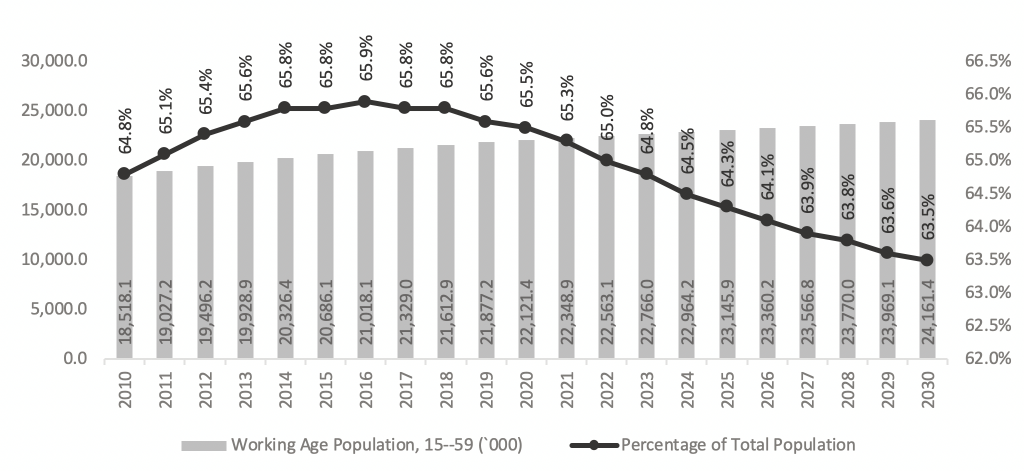

Working age population and its size relative to total population, Malaysia, 2010 to 2030

Source: Ipsos Analysis, based on DOSM population projected data (revised)

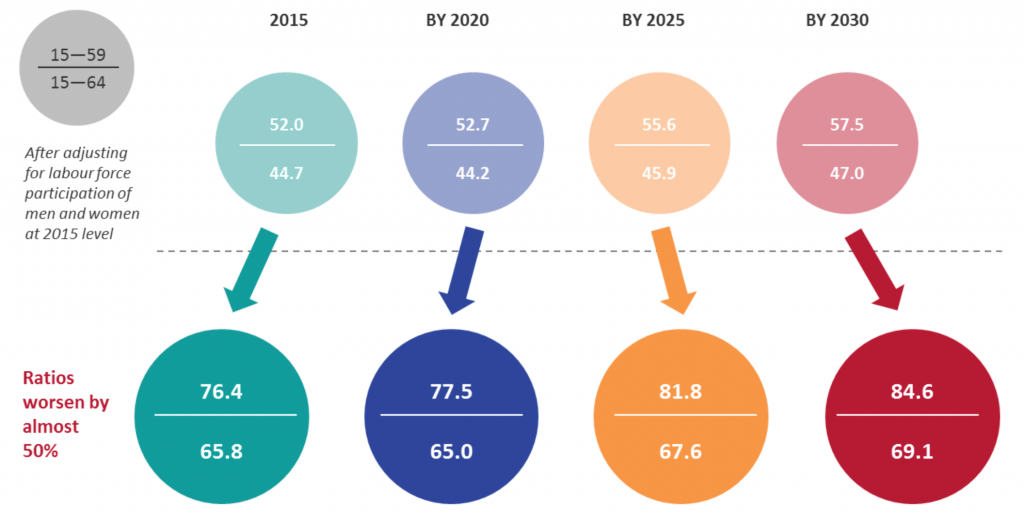

As the relative size of the working age population decreases by 2030 compared to the total population, dependency ratio increases; in this situation, it becomes even more critical that the productivity of the working-age population is maximised, and a high labour force participation is developed. Assuming that the labour force participation maintains at 2016 levels , the dependency ratio will worsen by nearly 50% by 2030, all things being equal.

Impact of labour force participation rate (2015) on dependency ratio

Source: Ipsos Analysis, based on DOSM population forecasted data and LFPR from Labour Force Survey

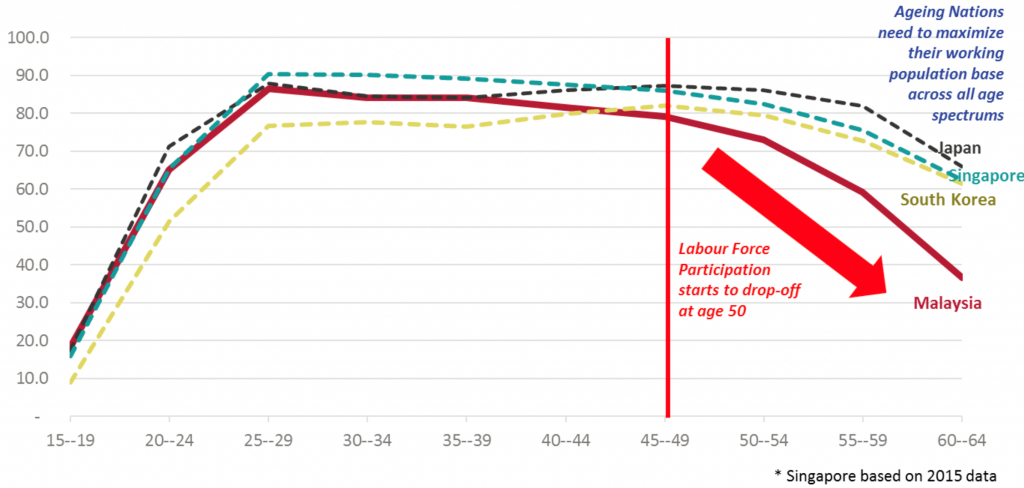

Labour force participation rate by age group, Malaysia and Selected Countries, 2016

Source: Ipsos Analysis, Malaysian data based on Labour Force Survey, other country’s data based on ILOSTAT

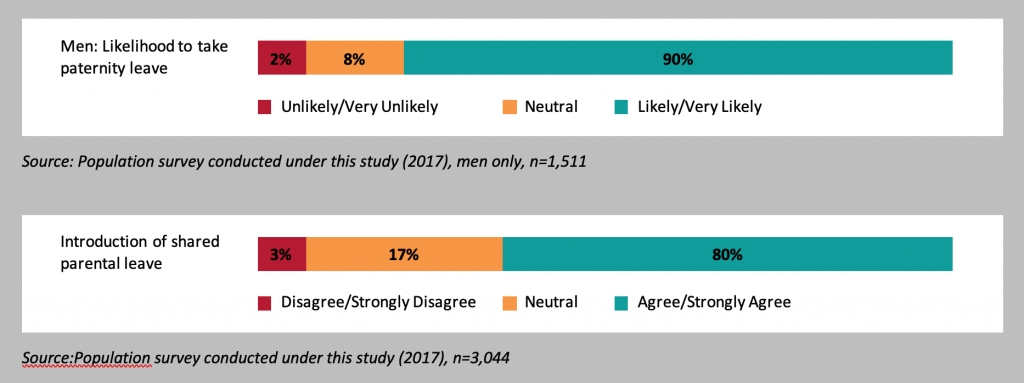

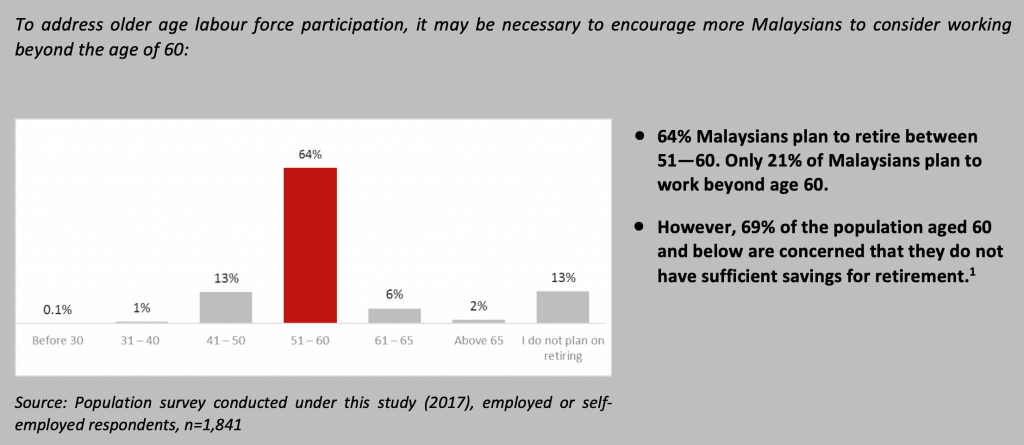

The labour force participation rate should be maximised in the following order: (A) Women. Presently, only 54% of Malaysian working age women are participating in the labour force. This represents the largest group of untapped labour. Of the women who are outside the labour force, about half of them do so because of family care responsibilities; (B) Youths. The unemployment rate for youths aged 15—24 was 10.5% in 2016, more than 3x higher than the national unemployment rate (3.4%); (C) Older age population. The labour force participation rate of population aged 45+ is low compared to other ageing nations such as Japan, Singapore, and South Korea.

The low labour force participation of older age population needs to be increased in order to sustain economic growth and lower social support burdens on government expenditure. In the case of Singapore, the government has recently increased the reemployment age up to 67 (retirement age is at 62). Conditions that are conducive and friendly for old age workers must be set into action today (e.g. removing barriers to employment, bridging skill gaps), such that the younger working age population, who will form the old age workforce by 2030, will be able to stay productive past 60.

Challenges to increase women’s labour force participation:

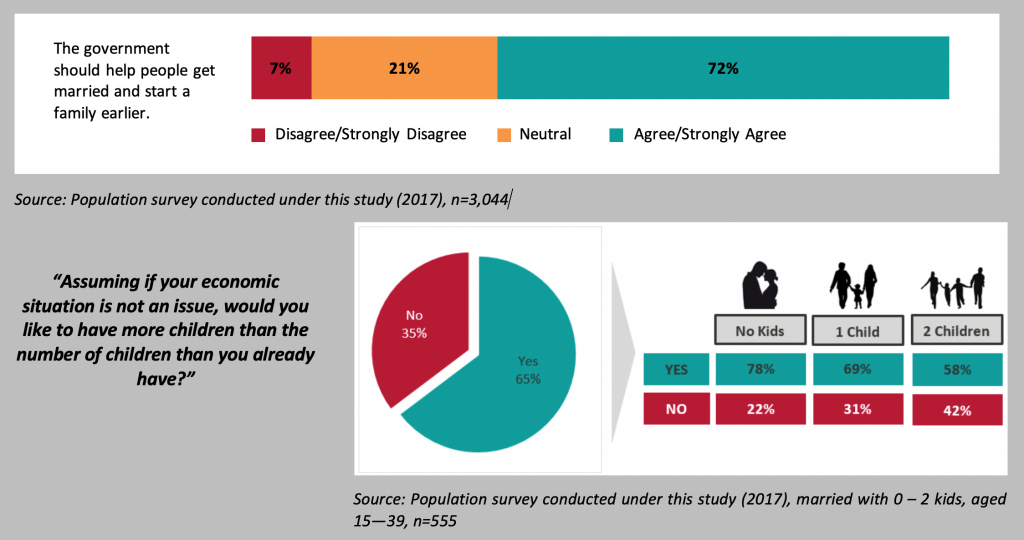

(9) Traditional family values are still strong. However, younger generations of Malaysians are increasingly more open to the idea of not having children.

Traditional family values cutting across perceptions on marriage, eldercare, and children among Malaysians of all generations are still relatively intact and strong. Malaysians desire to get married, have strong feelings of responsibility towards taking care of their elders, and believe that having children is a positive thing. The strong preservation of values particularly in the millennial generation (defined as those born between 1980 to 2000) indicate that, all things being equal, family values in 2030 will likely be very similar to family values of today. As such, the family type landscape in 2030 will likely be very similar to the present landscape as well.

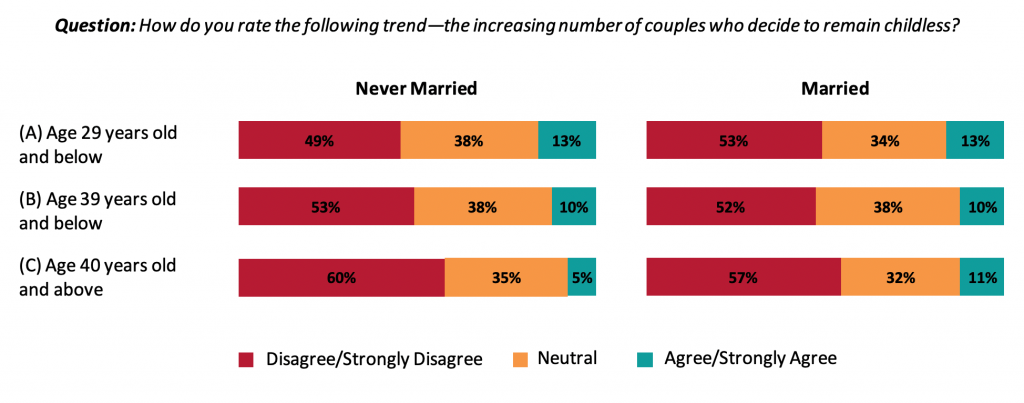

However, there is a significant difference between generations when it comes to tolerances about not having children.

Millennials are more open to the idea of not having children, with the younger millennials even more open, still.

Source: Population survey conducted under this study (2017). (A) Never Married, n=811; Married, n=232; (B) Never Married, n=112; Married, n=584; (C) Never Married, n=43; Married, n=1,172

(10) Nuclear and extended families will still be the dominant family types by 2030. However, the pressures of livelihood will become the primary shaper of how family members work and live together, as well as determining their level of health.

In terms of living arrangements, an overwhelmingly large number of Malaysians still prefer to live together under the union of marriage, while other living arrangements, such as cohabitation, are not popular. Historical data of household types also indicate a positive uptrend in nuclear and family households.

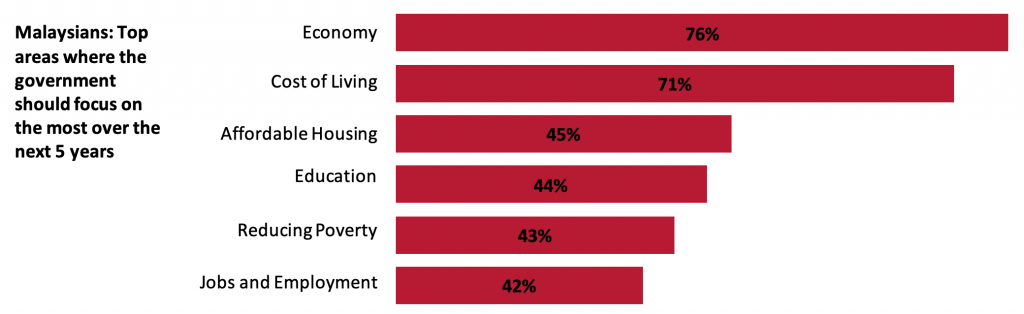

Nevertheless, Malaysians concerns about the economy and cost of living, if sustained, will drive families to work harder at the expense of the family.

The majority of families will increasingly need dual incomes to sustain themselves financially, encouraging the formation of commuter families ; nuclear families who are facing difficulties in making ends meet might ‘consolidate’ back into extended families, and in the case where elderlies and children are dependent on working adult parents, result in the formation of sandwich families. Generally, these living arrangements are not optimal. In the case of commuter families, the family environment is less conducive for childrearing, and may lead to an increase in psychosocial ailments such as depression among family members.

In the case of sandwich families, the juggling of care responsibilities between elderly and children will overburden adult parents.

Sandwich generation experiences increased family burden

| Shana is a 37-year-old teacher who is a working parent juggling between caring for her young children and ageing parent at the same time. She is part of the ‘Sandwich Generation’ comprised of millions of working adults generally aged between 35 to 54 who are raising children and helping to care for ageing parents. Sandwiched between the needs of her children and her parents, Shana has to stay on top of her two families simultaneously. “There is always something weighing on my mind, be it helping my kids with their studies or helping my mother to select a new pair of spectacles. Attending school functions or taking my mother for a check-up in the hospital. ”Despite this, she considers herself as one of the lucky ones as her children are responsible individuals and her mother is generally in good health. Besides that, her husband’s parents live with their eldest son and the pressure would have doubled if she had to care not just for her own parent but also her husband’s. As her mother receives her father’s monthly pension, Shana also realises how demanding it would have been if she had to cover both the expenses of her children and parent by herself. Nonetheless, even if things appear financially stable now, she is worried about the future considering her children’s college years and her mother’s need for additional at-home care. Source: Malaysia Digest (2016) |

Among Singaporeans and Malaysians, more time is spent at work rather than with families

| Most sectors in developing Southeast Asian countries are labour intensive in general, resulting in social impacts such as the lack of time to spend with families and to find love. About 63% of Malaysian workers have not been spending enough time with their family due to long working hours.[1]One respondent said, “Even if my company has work-life balance initiatives such as an on-site gym, a chill-out area and other organized social activities. It’s there in place just for show as we don’t even have sufficient manpower to sustain the workload.” Similarly, in Singapore, a recent poll conducted by Families for Life Council (FFL) revealed that long working hours was the top reason preventing locals from spending time with their families. 55% stated they are not satisfied with the amount of quality family time spent because of the hours they and their spouses spend at work. Simultaneously, 71% of the respondents felt spending time with their family gave them most happiness. Despite this, Singaporeans still feel obliged to work longer hours. One respondent explicitly stated that she would like Singaporean employers to “create a company culture that encourages employees to leave work on time”. Moreover, a study by Ipsos & SSI in end 2015 revealed that just 29% of Singaporeans professed to putting their needs first, while 64% said their families were of paramount importance, compared to just 55% in Malaysia. Source: News articles, secondary reports |

Malaysians are most concerned about the nation’s economy and the rising cost of living.

Source: Population survey conducted under this study (2017), n=3,044

(11) In the future, the largest change factor to the Malaysian way of life will be the interruption of technology. Families will need to learn to coexist with technology, while preserving the human touch.

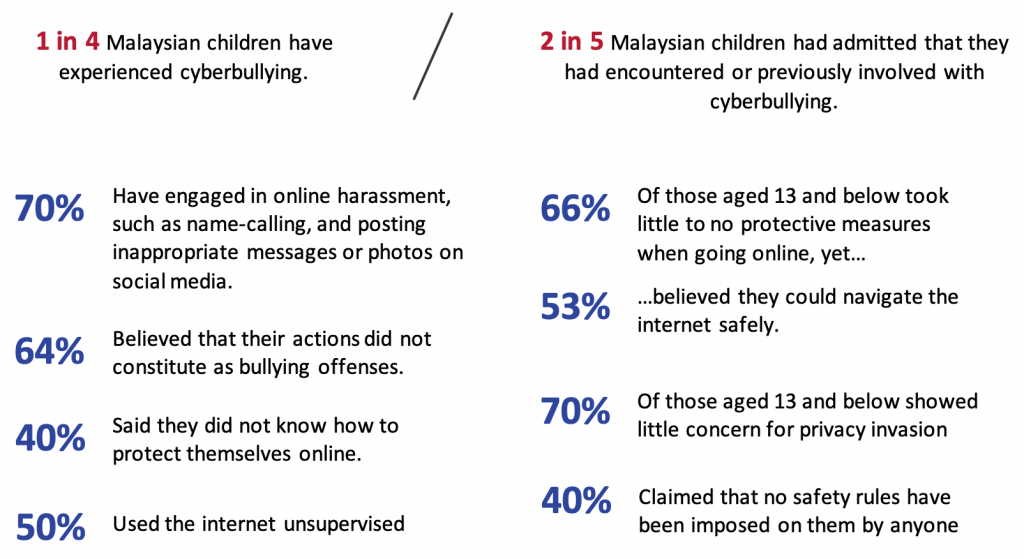

While technology is a great enabler of improving quality of life, the negative influences of technology need to be managed. The negative influences of technology can be seen today, through the rise of modern social ailments such as cyberbullying and sexting. In the future, robotics technology will be advanced enough to fully assume care duties for families. Presently, use cases for robot care for the elderly are being tested in Europe and also Japan. However, it is critical to keep in mind that healthy human relationships require human-to-human interaction. Future families will need to be equipped with knowledge on how to manage technology such that it doesn’t erode the humanistic aspects of family life.

The dichotomy between technology and Japan’s celibacy syndrome

| In Japan, there is a rising number of men and women under-40s who appear to be losing interest in conventional relationships. Millions of Japanese are not dating, and many are not bothered with sex. A survey in 2011 found that 61% of single men and 49% of single women aged 18—34 were not in any kind of romantic relationship. This trend has manifested itself into a national catastrophe, given that Japan already has one of the lowest fertility rates in the world, and its population is projected to shrink by another 1/3 in 2060. The celibacy syndrome is a complex social issue arising from cultural, economic, and environmental factors, including the use of technology. For example, holographic technology has progressed to a stage where a virtual assistant is ‘replacing’ the housewife, targeted at lonely Japanese men. An increasing number of celibate Japanese women prefer ‘dating’ virtual men, who are ‘perfect’, compared to dating in real life. On one hand, technology is able to provide intimacy for the celibate generation of Japan; on the other hand, it is not contributing towards efforts to address the social problem. Source: News articles, secondary reports |

The prevalence of cyberbullying in Malaysia

Source: Cybersafe Survey 2014

Contraceptive Prevalence Rate CPR rate has maintained at about 52%, despite the declining TFR. Based on survey findings, Malaysians do not consider abortion as a preferred pregnancy prevention method [3] .Two likely possibilities that can better explain the phenomena are (1) The relatively high prevalence of sub-fertility[4]; (2) The relatively low frequency of sex among married couples.[5]

Infant Mortality Rate The total under-5 mortality rate was 8.4 per 1,000 live births in 2015, significantly higher than developed nations such as Singapore (3), Japan (3), and Finland (2).[6]Infant mortality is the largest contributor to the total under-5 mortality rate at 6.9 per 1,000 live births. Lowering infant mortality will have a positive impact on raising TFR.

Universal Homes Universal home designs for elderly in Malaysia are still at infancy stages, compared to developed nations such as Australia. The proportion of Malaysian population who are ageing is expected to increase in the near future and will result in the need for modifications to the physical layout and features of many homes, especially for long-term stay.[7]

Quality of Life Gap in Disadvantaged Families Disadvantaged families, such as single parent families and families burdened with long term care (PWD), particularly those in B40 families, are still concerned about the future of their families at the basic level.[8] They are at risk of being left behind.

ICT Skills Proficiency Within ASEAN, Malaysia ranks above the ASEAN average in terms of the ICT Skills Index (Malaysia 5.9, ASEAN average 5.2)[9]. However, Malaysia still ranks behind Philippines (6.1), Thailand (6.2), Brunei (6.3), and Singapore (7.3). Malaysians will need to gain higher proficiencies in order to be competitive in the economies of the future.

Sustainable Best Practices Sustainable best practices are still viewed as ‘options’ as opposed to a way of life. In particular, the areas which Malaysia needs to focus on improving are (A) 3R practices; (B) Food waste reduction; (C) Conservation of water consumption; and (D) E-waste management, which will be a future concern.

Selected Additional Findings [3] Only 3% of Malaysians aged 15—49 will use abortion as a pregnancy prevention method; 84% will not (Population survey conducted under this study (2017), n=2,258). [4] 25% of Malaysians state that they have difficulties conceiving a child, i.e. actively trying for 1 year but without success (Population survey conducted under this study (2017), n=3,044) [5] In 2014, Malaysian married couples are having sex 64x in a year on average, compared to the global average of 103x a year.[6] See page 116 for data sources. [7] See Appendix F, page 257