Malaysia Population Research Hub

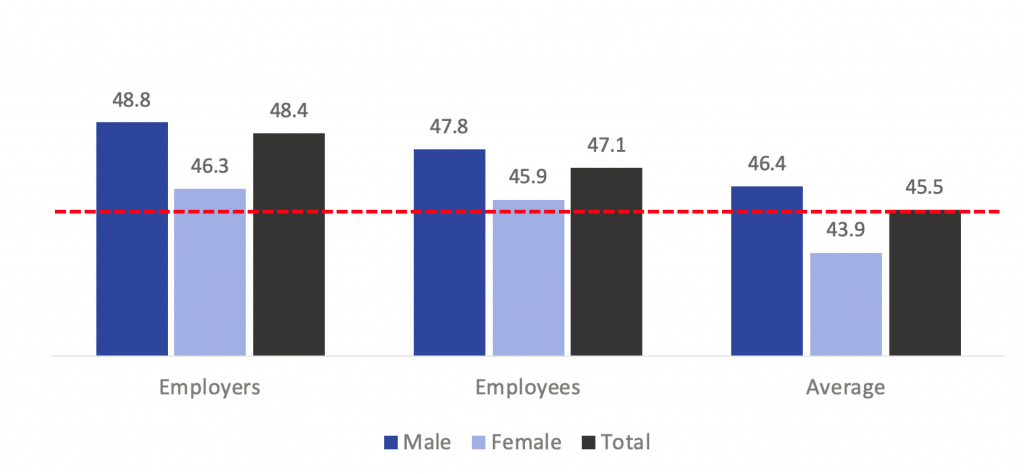

Malaysians, in general, work longer hours on an average work week compared to the OECD countries. (In 2016, Malaysia mean hours per workweek is 45.4 hours, which is much longer than the OECD average of 33.9 hours. Malaysian employers work on average about 48.8 hours while employees work on average about 47.8 hours per week). Malaysian average working hours nearly reach the boundaries of standard of excessive working hours of 48 hours, which is 20% of extra working hours from the recommended standard 40 hours per workweek.

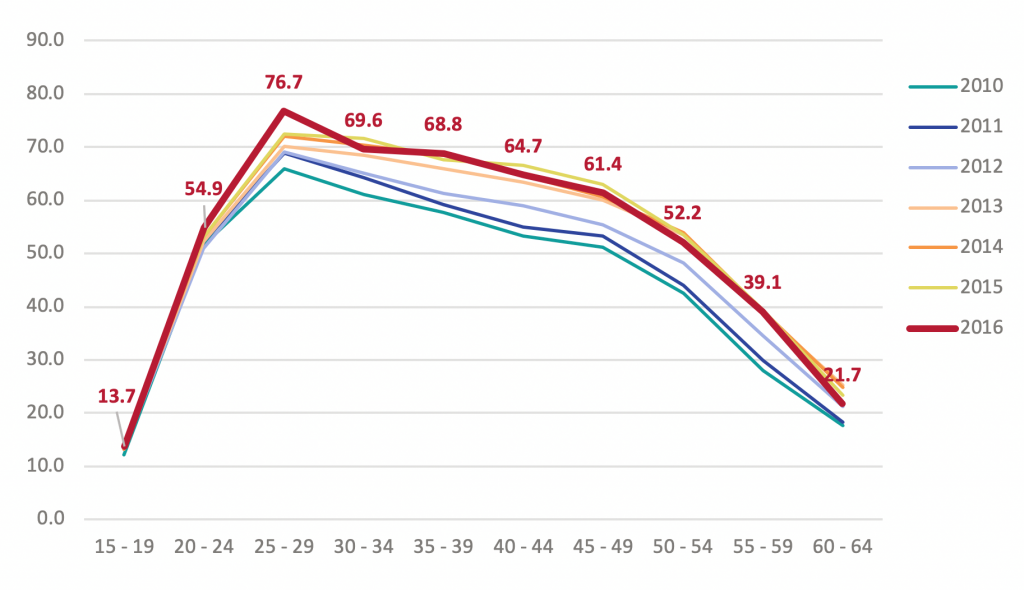

Even after career break, Malaysian women are not re-joining the workforce

Despite gradual improvement, the female labour force participation in the country is still low, primarily driven by traditional gender role and caregiving responsibilities at home which hinder women from participating in the economy. Many mothers face difficulties in returning to work after taking a career break to start a family and raise their children. (Although the LFPR of Malaysian women has improved, similar trend is observed over the years, whereby the LFPR is single peaked and begins to drop from age 30 years onwards. This is opposed to double peaked LFPR in countries such as Japan or South Korea, where most women managed to re-join the workforce after taking a career break).

Malaysians feel that the government can help to enable shared parental and caregiving responsibilities through shared parental leaves.

The labour force participation of older population is low, for a nation that will soon be ageing

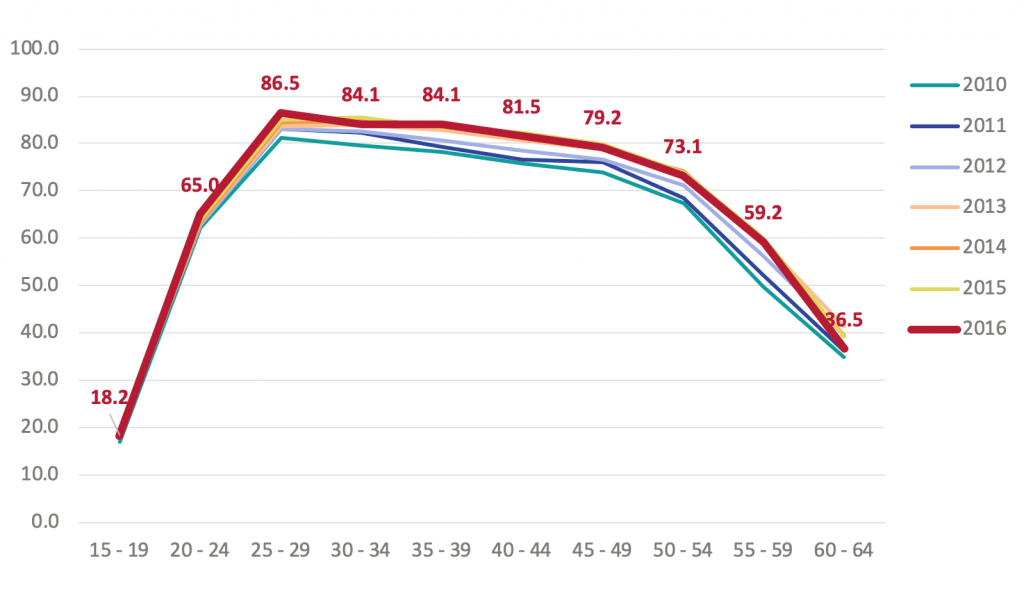

Despite increasing life expectancy and aging of the population, Malaysia still have a relatively low labour force participation of the population aged 50 and above compared to aged countries. (LFPR of population aged 50 and above in Malaysia is well below 60, while that of countries such as South Korea, Japan and Singapore are above 70, on average).The national labour force participation has improved slightly, however, similar trend persists over the years in terms of economic participation of mature workers.

The national labour force participation rate starts to decline significantly from age 50 years onwards as a great majority of the Malaysian population prefers to retire between 51 to 60 years old.

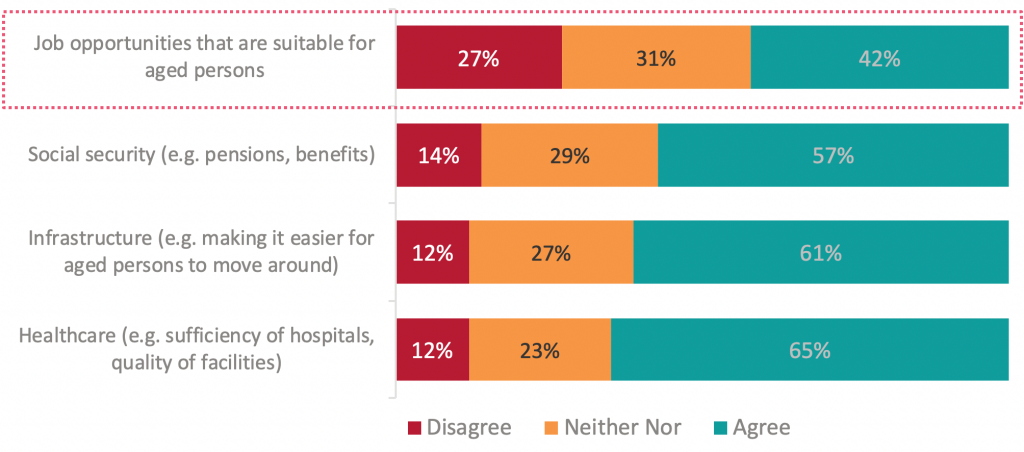

Malaysians find that suitable jobs for the elderly are lacking in the country

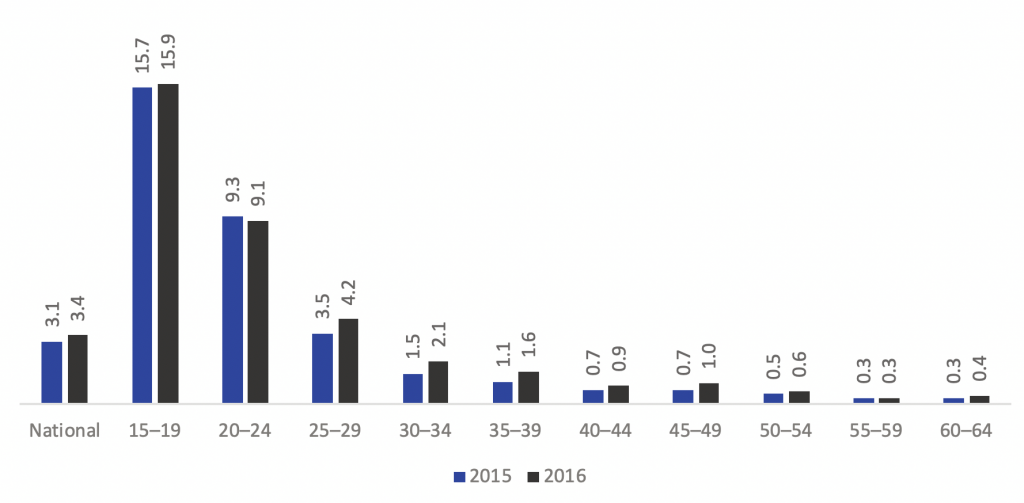

Youth unemployment lengthens road to economic security for future families

Youth unemployment, defined as unemployment of those aged 15 – 24, is a major concern when compared to unemployment in other age groups. While youth unemployment is not just a Malaysian problem (countries around the world are also struggling with it), the issue does not warrant less attention, as youth unemployment impacts not only the socio-economy landscape, but also many aspects of the family as the youth progresses along his or her life course (such as, for example, marriage and time of first childbirth ). Youth unemployment over extended periods of time slows down the accumulation of knowledge and experience, which in turn slows down future career progression and delays the achievement of maximum economic security once the family is formed. In Malaysia context, of particular concern is graduate unemployment.

(Compared to 2010, the respective figures were 26% for those unemployed with tertiary education and 17% for those unemployed with at least a diploma certification or higher. )

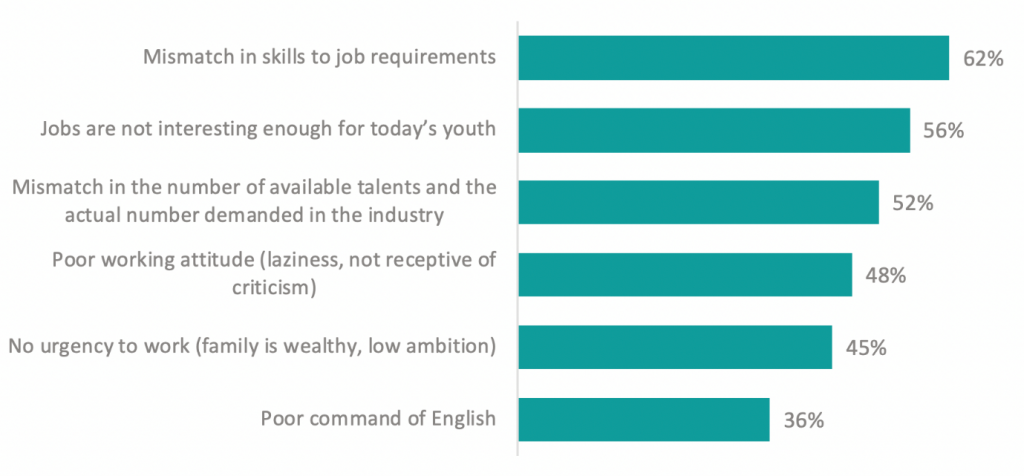

Youth unemployment in Malaysia is mainly attributed to the mismatch in skills and talents, along with the lack of interesting jobs for the youth.

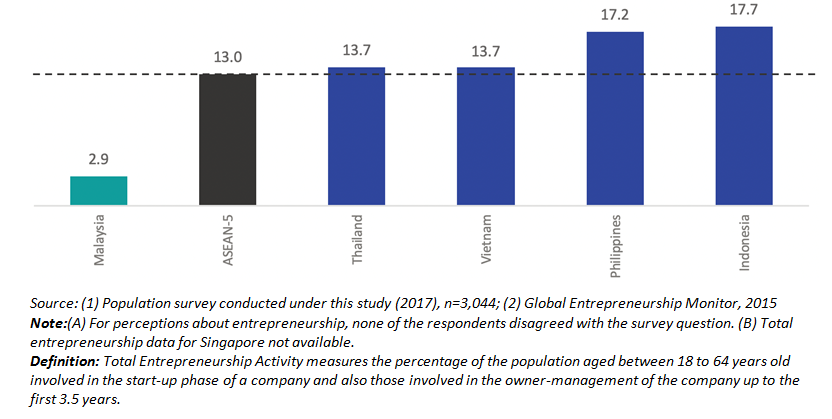

Despite Malaysians think positively about entrepreneurship, take-up rate is lower than desired

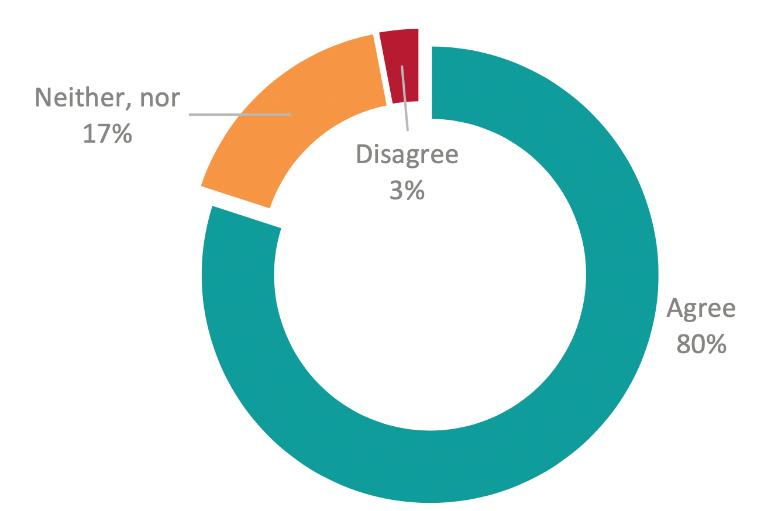

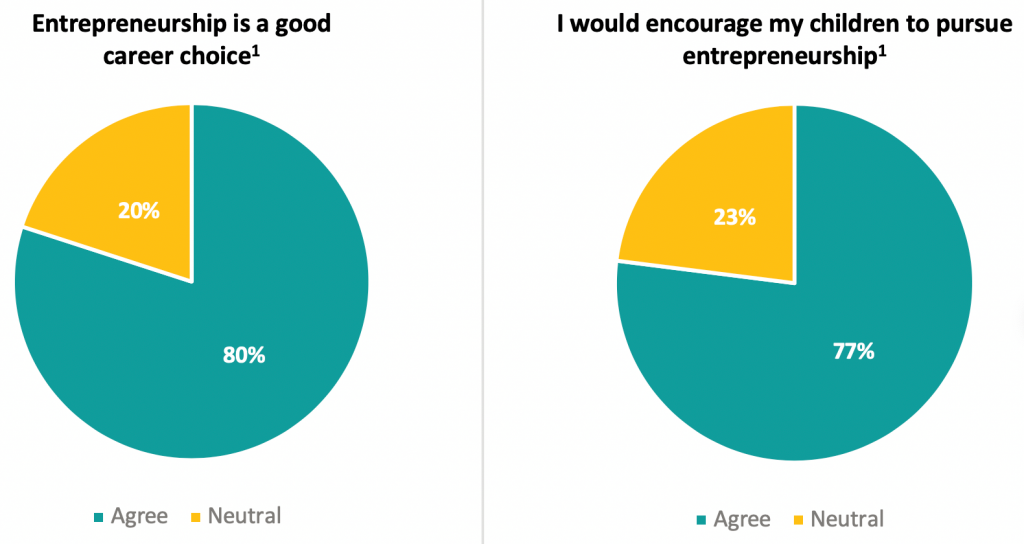

Overall, entrepreneurship is viewed positively by Malaysians. 80% of Malaysians believe that entrepreneurship is a good career choice. Furthermore, 77% of Malaysians said that they would encourage their children to pursue entrepreneurship.

However, entrepreneurship take-up rate in Malaysia is considerably lower compared to its ASEAN nations.

(According to Global Entrepreneurship Monitor in 2015, the total entrepreneurship activity in Malaysia was just 2.9% for those aged between 18â€â€64 compared to the ASEAN average of 13.0%.)

Total Entrepreneurship Activity (% of Population Aged 18 – 24)